INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING APPLICATIONS IN FINANCIAL ASSET MANAGEMENT:NEW ASSET CLASSES

NEW ASSET CLASSES

A virtually endless stream of new investment products is paraded forth by financial service companies each year. Although promoted as innovative with superlative benefits, in reality most such creations are often narrowly focused with high risk or are reconfigured and redundant transformations of assets already available. Sorting through the muck and discovering innovative products that shift the efficient frontier outward is not an easy task

Desirable Asset Characteristics

In general, new assets that effectively shift the efficient frontier outward must possess differential return and risk profiles, and have low correlation with the existing assets in the portfolio. Incorporating an asset that has similar returns and risk and is collinear with an asset already in the portfolio is duplicative. One needs only one of the two.

Differential returns, risk, and correlation are not enough, however. A new asset that has a lower return and significantly higher volatility will not likely enter optimal portfolios even if it has a low correlation with existing assets. In contrast, a new asset with a higher return, lower risk, and modest correlation with existing assets will virtually always enter at least some of the optimal portfolios on the efficient frontier.

In decades past, adding real estate, commodities, and gold to stock and bond portfolios produced the desired advantages. Low returns for these assets in the 1980s and subsequent years led to their eventual purging from most portfolios by the mid-1990s. They were replaced with assets such as international stocks and bonds, emerging market securities, and high-yield debt.

Today, most managers employ multiple equity classes in their portfolios to achieve asset diver- sification. They usually include U.S. as well as international and emerging market stocks. Some managers split the U.S. equities category into large, midsized, and small capitalization securities, or alternatively into growth and value stocks. Some managers use microcap stocks. The fixed-income assets commonly used include U.S. bonds, international bonds, high-yield debt, and emerging market debt. Some managers further break U.S. bonds into short, medium, and long-duration ‘‘buckets.’’ A

few investment managers retain real estate as an investable asset, while a smaller minority includes commodities as an inflation hedge.

One problem is that the correlation between different equity and fixed income subcategories is fairly high. Thus, the advantages gained from dividing equities and fixed income into components are not that great. In fact, cross-market correlation has increased recently due to globalization. For example, the performance of large, small, and midcap equities, as well as that of international equities, now moves much more in parallel than in the past.

Where are the new opportunities to improve portfolio performance by creatively expanding the investable asset domain? There are several assets that are now increasingly accepted and utilized in portfolios. The most important are hedge funds, private equity, and venture capital. Other new assets have shown the ability to improve portfolio performance but for various reasons have not yet made the leap to widespread recognition. These include inflation-protected securities and insurance-linked products.

Hedge Funds

Over the last several years, hedge funds have garnered tremendous attention as an attractive addition to classic stock and bond portfolios. A virtual avalanche of published MV studies indicates that hedge funds extend the efficient frontier. Examples include research by Agarwal and Naik (2000), Lamm and Ghaleb-Harter (2000b), Lamm (1999a), Purcell and Crowley (1999), Edwards and Lieu (1999), and Schneeweis and Spurgin (1999). Other work supporting the inclusion of hedge funds in portfolios was done by Tremont Partners and TASS Investment Research (1999), Goldman Sachs and Financial Risk Management (1999), Yago et al. (1999), Schneeweis and Spurgin (1998), and Fung and Hseih (1997). The general conclusions are that substantial hedge fund allocations are appropriate, even for conservative investors.

All of these studies presume that hedge fund exposure is accomplished via broad-based portfolios. That is, like equities, hedge fund investments need to be spread across a variety of managers using different investment strategies. This means at least a dozen or more. Investing in only one hedge fund is an extremely risky proposition, much like investing in only one stock.

The primary advantage of hedge fund portfolios is that they have provided double-digit returns going back to the 1980s with very low risk. Indeed, hedge fund portfolio volatility is close to that of bonds. With much higher returns and low correlation compared with traditional asset classes, they exhibit the necessary characteristics required to enhance overall portfolio performance.

Hedge funds are private partnerships and are less regulated than stocks. For this reason, a strict due diligence process is essential to safeguard against the rare occasion when unscrupulous managers surface. Because most investors cannot or do not want to perform comprehensive evaluations of each hedge fund, funds of hedge funds are increasingly used as implementation vehicles. Large investment banks or financial institutions usually sponsor these funds. They have professional staffs capable of performing a laborious investigative and review process.

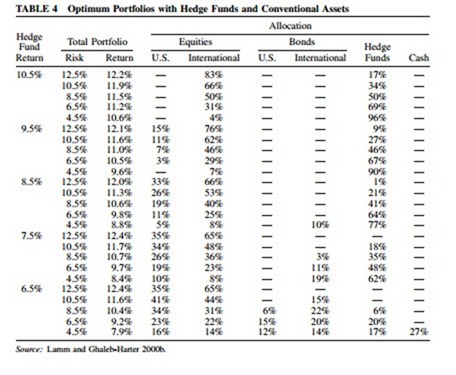

Table 4 reproduces the results of a MV optimization by Lamm and Ghaleb-Harter to assess the impact of adding hedge funds to portfolios of traditional assets. Results are given for a conservative range of prospective hedge fund returns varying from 6.5–10.5%. The volatility of the hedge fund portfolio is close to 4%, not much different from history. The assumed correlation with stocks and bonds is 0.3, also close to historical experience. The other assumptions are similar to those presented in the Section 3 example.

The key findings are that (1) hedge funds primarily substitute for bonds and (2) substantial allocations are appropriate for practically all investors, even conservative ones. This is true even if relatively low hedge fund returns are assumed. The conclusion that hedge funds are suitable for conservative investors may be counterintuitive to many readers, who likely perceive hedge funds as very risky investments. However, this result is now strongly supported by MV analysis and occurs primarily because hedge fund managers practice diverse investment strategies that are independent of directional moves in stocks and bonds. These strategies include merger and acquisition arbitrage, yield curve arbitrage, convertible securities arbitrage, and market-neutral strategies in which long positions in equities are offset by short positions.

In response to recent MV studies, there has been a strong inflow of capital into hedge funds. Even some normally risk-averse institutions such as pension funds are now making substantial al- locations to hedge funds. Swensen (2000) maintains that a significant allocation to hedge funds as well as other illiquid assets is one of the reasons for substantial outperformance by leading university endowment funds over the last decade.

Private Equity and Venture Capital

As in the case of hedge funds, managers are increasingly investing in private equity to improve portfolio efficiency. Although there is much less conclusive research on private equity and investing, the recent performance record of such investments is strong.

There are varying definitions of private equity, but in general it consists of investments made by partnerships in venture capital (VC) leveraged buyout (LBO) and mezzanine finance funds. The investor usually agrees to commit a minimum of at least $1 million and often significantly more. The managing partner then draws against commitments as investment opportunities arise.

In LBO deals, the managing partner aggregates investor funds, borrows additional money, and purchases the stock of publicly traded companies, taking them private. The targeted companies are then restructured by selling off noncore holdings, combined with similar operating units from other companies, and costs reduced. Often existing management is replaced with better-qualified and ex- perienced experts. After several years, the new company is presumably operating more profitably and is sold back to the public. Investors receive the returns on the portfolio of deals completed over the partnership’s life.

The major issue with private equity is that the lock-up period is often as long as a decade. There is no liquidity if investors want to exit. Also, because the minimum investment is very high, only high-net-worth individuals and institutions can participate. In addition, investments are often concen- trated in only a few deals, so that returns from different LBO funds can vary immensely. Efforts have been made to neutralize the overconcentration issue with institutions offering funds of private equity funds operated by different managing partners.

VC funds are virtually identical in structure to LBO funds except that the partnership invests in start-up companies. These partnerships profit when the start-up firm goes public via an initial public offering (IPO). The partnership often sells its shares during the IPO but may hold longer if the company’s prospects are especially bright. VC funds received extraordinary attention in 1999 during the internet stock frenzy. During this period, many VC funds realized incredible returns practically overnight as intense public demand developed for dot-com IPOs and prices were bid up speculatively.

Because LBO and VC funds are illiquid, they are not typically included in MV portfolio optim- izations. The reason is primarily time consistency of asset characteristics. That is, the risk associated with LBOs and VC funds is multiyear in nature. It cannot be equated directly with the risk of stocks, bonds, and hedge funds, for which there is ample liquidity. A less egregious comparison requires multiyear return, risk, and correlation calculations.

Inflation-Protected Securities

Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPs) are one of the most innovative financial products to appear in recent years. They pay a real coupon, plus the return on the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Thus, they automatically protect investors 100% against rising inflation, a property no other security possesses. Further, in a rising inflation environment, returns on TIPs are negatively correlated with those of bonds and other assets whose prices tend to decline when inflation rises.

In an MV study of combining TIPs with conventional assets, Lamm (1998a, b) finds that an overweighting in these securities vs. traditional bonds is appropriate only when inflation is expected to rise. He suggests a 50 / 50 weighting vs. traditional bonds when inflation direction is uncertain and underweighting when inflation is expected to fall.

In years past, some investment managers touted gold, commodities, or real estate as inflation hedges. The availability of TIPs neutralizes arguments made in favor of these ‘‘real’’ assets because their correlation with inflation is less than perfect. TIPs provide a direct one-to-one hedge against rising inflation.

Despite the attractive characteristics of TIPs, they have met with limited market acceptance. This is a consequence partly of a lack of awareness but also because TIPs significantly underperformed conventional Treasury securities as inflation declined immediately after their introduction in 1997. However, for the first time in years, inflation is now rising and TIPs have substantially outperformed Treasuries over the last year. This will likely change investor attitudes and lead to greater acceptance of the asset class.

Other Assets

Another new asset proposed for inclusion in portfolios is insurance-linked products such as catastro- phe bonds. These securities were evaluated in MV studies done by Lamm (1998b,1999b). They are issued by insurance companies as a way of protecting against heavy losses that arise as a consequence of hurricanes or earthquakes. The investor receives a large payoff if the specified catastrophe does not occur or a low return if they do. Because payoffs are linked to acts of nature, the correlation of insurance-linked securities with other assets is close to zero. Unfortunately, the market for insurance- linked securities has failed to develop sufficient liquidity to make them broadly accessible to investors.

Another asset occasionally employed by investment managers is currency. While currencies meet liquidity criteria, their expected returns are fairly low. In addition, exposure to foreign stocks and bonds contains implicit currency risk. For this reason, currencies are not widely viewed as a distinct standalone asset. Even managers that do allocate to currencies tend to view positions more as short- term and tactical in nature.

Finally, there are a number of structured derivative products often marketed as new asset classes. Such products are usually perturbations of existing assets. For example, enhanced index products are typically a weighted combination of exposure to a specific equities or bond class, augmented with exposure to a particular hedge fund strategy. Similarly, yield-enhanced cash substitutes with principal guarantee features are composed of zero coupon Treasuries with the residual cash invested in options or other derivatives. Such products are part hedge fund and part primary asset from an allocation perspective and are better viewed as implementation vehicles rather than incorporated explicitly in the asset allocation.

Comments

Post a Comment