LEADERSHIP, MOTIVATION, AND STRATEGIC HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT:LEADERSHIP AND MOTIVATION

LEADERSHIP AND MOTIVATION

The Classic Paradigm of Leadership: A Transactional Approach I was his loyal friend, but no more. . . . I was so hurt when I discovered that in spite of my loyalty, he always preferred Arie Dery to me. I asked him: ‘Bibi, why? ’ and he answered: ‘‘He brings me 10 seats in the parliament while you don’t have such a bulk of voters behind you.’’

—Itzhak Levi, former Minister of Education, on Benjamin Netanyahu, former Prime Minister of Israel Many of the classic approaches to leadership concentrated on how to maintain or achieve results as expected or contracted between the leader and the employees. These transactional theories and practices viewed leadership in terms of contingent reinforcement, that is, as an exchange process in which employees are rewarded or avoid punishment for enhancing the accomplishment of agreed- upon objectives.

Figure 2 shows the process by which transactional leaders affect their employees’ motivation and performance. Transactional leaders help employees recognize what the role and task requirements are to reach a desired outcome. The transactional leader helps clarify those requirements for em- ployees, resulting in increased confidence that a certain level of effort will result in desired perform- ance. By recognizing the needs of employees and clarifying how those needs can be met, the transactional leader enhances the employee’s motivational level. In parallel, the transactional leader recognizes what the employee needs and clarifies for the employee how these needs will be fulfilled in exchange for the employee’s satisfactory effort and performance. This makes the designated out- come of sufficient value to the employee to result in his or her effort to attain the outcome. The model is built upon the assumption that the employee has the capability to perform as required. Thus, the expected effort is translated into the expected performance (Bass 1985).

There is support in the literature for the effectiveness of transactional leadership. Using contingent reinforcement, leaders have been shown to increase employee performance and job satisfaction and to reduce job role uncertainty (Avolio and Bass 1988). For example, Bass and Avolio (1993) report results collected from 17 independent organizations indicating that the correlations between the con- tingent reward leadership style and employees’ effectiveness and satisfaction typically ranged from to 0.6, depending on whether it was promises or actual rewards. Similarly, Lowe et al. (1996), in their meta-analysis of 47 studies, report that the mean corrected correlation between contingent reward and effectiveness was 0.41.

Although potentially useful, transactional leadership has several serious limitations. First, the contingent rewarding, despite its popularity in organizations, appears underutilized. Time pressure, poor performance-appraisal systems, doubts about the fairness of the organizational reward system, or lack of managerial training cause employees not to see a direct relationship between how hard they work and the rewards they receive. Furthermore, reward is often given in the form of feedback from the superior, feedback that may also be counterproductive. What managers view as valued feedback is not always perceived as relevant by the employees and may be weighted less than feedback received from the job or coworkers. In addition, managers appear to avoid giving negative feedback to employees. They distort such feedback to protect employees from the truth. Second, transactional leadership may encourage a short-term approach toward attaining organizational objec-

tives. A transactional leader who views leadership solely from a contingent reinforcement perspective may find that employees will circumvent a better way of doing things to maximize short-term gain to reach their goals in the most expeditious manner possible, regardless of the long-term implications. Third, employees do not always perceive contingent reinforcement as an effective motivator. The impact may be negative when the employees see contingent rewards given by the superior as ma- nipulative (Avolio and Bass 1988).

Finally, one of the major criticisms directed toward this contract-based approach to leadership has been that it captures only a portion of the leader-follower relationships. Scholars like Hemphill (1960) and Stogdill (1963) (in Seltzer and Bass 1990) felt long ago that an expanded set of factors was necessary to fully describe what leaders do, especially leader–follower relationships that include motivation and performance that go beyond contracted performance. Bass and Avolio (1993) state that the ‘‘transaction’’ between a leader and a follower regarding the exchange of rewards for achiev- ing agreed-upon goals cannot explain levels of effort and performance of followers who are inspired to the highest levels of achievement. There are many examples of leadership that do not conform to the ever-popular notion of a transaction between leader and follower. As Howell (1996) points out, the notion of leaders who manage meaning, infuse ideological values, construct lofty goals and visions, and inspire was missing entirely from the literature of leadership exchange. A new paradigm of leadership was needed to account for leaders who focus the attention of their employees on an idealized goal and inspire them to transcend themselves to achieve that goal. The actions of such leaders result in higher-order changes in employees and therefore in higher performance.

The New Paradigm of Leadership: A Transformational Approach Head in the clouds, feet on the ground, heart in the business.

of her credentials include winning the first-ever Olympic gold medal in U.S. women’s basketball history; six national championships; an .814 winning percentage, fifth among all coaches in college basketball history; and so many trips to basketball’s Final Four that her record in all likelihood will never be equaled. Her 1997–1998 University of Tenessee team finished the regular season 30 and 0 and won its third consecutive national title. Beyond coaching records, however, what is Summitt like as a person? Among other things, when she walks into a room, her carriage is erect, her smile confident, her manner of speaking direct, and her gaze piercing. Her calendar documents her pressured schedule. But she is also a deeply caring person, appropriate for a farm daughter who grew up imitating her mother’s selfless generosity in visiting the sick or taking a home-cooked dinner to anyone in need. Summitt clearly has many extraordinary qualities as a coach, but perhaps most striking is the nature of the relationship she develops with her players (Hughes et al. 1998). Pat Summitt does not rely only on her players’ contracts to gain their highest levels of motivation and performance. The best transactional, contract-based leadership cannot assure such high performance on the part of the players. Summitt clearly has the additional qualities of what is referred to as transformational leadership.

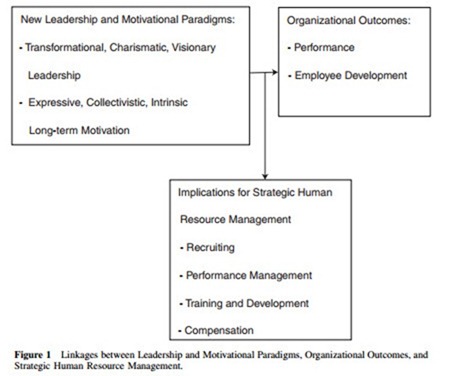

Indeed, the past 15 years have seen some degree of convergence among organizational behavior scholars concerning a new genre of leadership theory, alternatively referred to as ‘‘transformational,’’ ‘‘charismatic,’’ and ‘‘visionary.’’ Transformational leaders do more with colleagues and followers than set up simple transactions or agreements (Avolio 1999). Transformational leadership theory explains the unique connection between the leader and his or her followers that accounts for extraordinary performance and accomplishments for the larger group, unit, and organization (Yammarino and Du-binsky 1994), or, as stated by Boal and Bryson (1988, p. 11), transformational leaders ‘‘lift ordinary people to extraordinary heights.’’ Transformational leaders engage the ‘‘full’’ person with the purpose of developing followers into leaders (Burns 1978). In constrast to transactional leaders, who seek to satisfy the current needs of followers through transactions or exchanges via contingent reward be- havior, transformational leaders (a) raise the follower level of awareness about the importance of achieving valued outcomes, a vision, and the required strategy; (b) get followers to transcend their own self-interests for the sake of the team, organization, or larger collectivity; and (c) expand the followers’ portfolio of needs by raising their awareness to improve themselves and what they are attempting to accomplish. Transformational leaders encourage followers to develop and perform at levels above what they may have felt was possible, or beyond their own personal expectations (Bass and Avolio 1993).

Perhaps the major difference between the new paradigm of leadership and the earlier classic approaches mentioned above lies in the nature of the relationships that are built between leaders and employees, that is, the process by which the leaders energize the employees’ effort to accomplish the goals, as well as in the type of goals set. According to the new genre of leadership theory, leaders transform the needs, values, preferences, and aspirations of the employees. The consequence of the leader’s behaviors is emotional and motivational arousal of the employees, leading to self- reinforcement mechanisms that heighten their efforts and bring performance above and beyond the call of duty or contract (Avolio and Bass 1988; House and Shamir 1993).

Differences in the Motivational Basis for Work between the Classic and the New Leadership Paradigms Individuals may approach social situations with a wide range of motivational orientations. The classic transactional and the new transformational paradigms of leadership differ in their assumptions about the core underlying bases for motivation to work. The main shifts in the motivational basis for work concentrate on three dimensions. The first deals with a transition from a calculative–rational toward an emotional–expressive motivation. The second concerns the shift from emphasizing individualistic- oriented motivation toward stressing the centrality of collectivistic-oriented motivation. The third dimension refers to the importance given to intrinsic motivators in addition to the traditional extrinsic incentives.

From a Calculative–Rational toward an Emotional–Expressive Motivation to Work The transactional approach to leadership is rooted in behavioral and contingency theories. This trans- actional paradigm is manifested in the long fixation on the dimensions of consideration or people- orientation and initiating structure or task-orientation (review in Yukl 1998). Leadership behavior, as measured by the indexes of initiating structure and consideration, is largely oriented toward accom- plishing the tasks at hand and maintaining good relationships with those working with the leader (Seltzer and Bass 1990). When the superior initiates structure, this enhances and reinforces the employees’ expectancy that their efforts will succeed. Consideration by the superior is a desired benefit reinforcing employee performance (Bass 1985). This transactional approach was also carried into contingency theories such as the path–goal theory of leadership developed by House (1971). The path–goal theory took as its underlying axioms the propositions of Vroom’s expectancy theory, which was the prevailing motivational theory at that time. According to expectancy theory, employees’ efforts are seen to depend on their expectancy that their effort will result in their better performance, which in turn will result in valued outcomes for them (Yukl 1998). The path–goal theory to leadership asserted that ‘‘the motivational function of the leader consists of increasing personal payoffs to subordinates for work-goal attainment and making the path to these payoffs easier travel by clarifying it, reducing roadblocks and pitfalls, and increasing the opportunities for personal satisfaction en route’’ (House 1971, p. 324). The common denominator of the behavioral and contingency approaches to leadership is that the individual is assumed to be a rational maximizer of personal utility. They all explain work motivation in terms of a rational choice process in which a person decides how much effort to devote to the job at a given point of time. Written from a calculative-instrumental perspective, discussions and applications of work motivation have traditionally emphasized the reward structure, goal structure, and task design as the key factors in work motivation and deemphasized other sources of motivation. Classic theories assume that supervisors, managers, leaders, and their followers are able to calculate correctly or learn expected outcomes associated with the exercise of theoretically specified behaviors. These theories, then, make strong implicit rationality assumptions despite sub- stantial empirical evidence that humans are subject to a myriad of cognitive biases and that emotions can be strong determinants of behavior (House 1995).

The new motivation and leadership paradigms recognize that not all of the relevant organizational behaviors can be explained on the basis of calculative considerations and that other considerations may enrich the explanation of human motivation (Shamir 1990). Transformational and charismatic leadership approaches assume that human beings are not only instrumental-calculative, pragmatic,

and goal-oriented but are also self-expressive of feelings, values, and self-concepts. We are motivated to do things because it makes sense to do them from a rational-instrumental point of view, but also because by doing so we can discharge moral obligations or because through such a contribution we can establish and affirm a cherished identity for ourselves. In other words, because it is useful, but also because it is right, or because it ‘‘feels right.’’ Making the assumption that humans are self- expressive enables us to account for behaviors that do not contribute to the individual self-interest, the most extreme of which is self-sacrifice (House and Shamir, 1993; Shamir 1990; Shamir et al. 1993). Huy (1999), in discussing the emotional dynamics of organizational change, refers to the emotional role of charismatic and transformational leaders. According to Huy, at the organizational level, the emotional dynamic of encouragement refers to the organization’s ability to instill hope among its members. Organizational hope can be defined as the wish that our future work situation will be better than the present one. Transformational leaders emotionally inspire followers through communication of vivid images that give flesh to a captivating vision so as to motivate them to pursue ambitious goals. The most important work for top managers is managing ideology and not strategy making. Transformational leaders can shape an ideological setting that encourages enthusiasm, nur- tures courage, reveals opportunities, and therefore brings new hope and life into their organizations.

Thus, classic leadership theories addressed the instrumental aspects of motivation, whereas the new paradigm emphasizes expressive aspects as well. Such emotional appeals can be demonstrated by the words of Anita Roddick, founder and CEO of The Body Shop:

Most businesses focus all the time on profits, profits, profits . . . I have to say I think that is deeply boring. I want to create an electricity and passion that bond people to the company. You can educate people by their passions . . . You have to find ways to grab their imagination. You want them to feel that they are doing something important . . . I’d never get that kind of motivation if we were just selling shampoo and body lotion. (Conger and Kanungo 1998, pp. 173–174)

From an Individualistic-Oriented toward a Collectivistic-Oriented Motivation to Work

Nearly all classic models of motivation in organizational behavior, in addition to being calculative, are also hedonistic. These classic approaches regard most organizational behavior as hedonistic and treat altruistic, prosocial, or cooperative behavior as some kind of a deviation on the part of the organizational members. This trend may be traced in part to the influence of the neoclassical paradigm in economics and psychology, which is based on an individualistic model of humans. American psychology, from which our work motivation theories have stemmed, has strongly emphasized this individualistic perspective (Shamir 1990).

The recent recognition that not all relevant work behaviors can be explained in terms of hedonistic considerations has led to the current interest in prosocial organizational behaviors, those that are formed with the intent of helping others or promoting others’ welfare. However, between totally selfish work behavior and pure altruistic behaviors, many organizationally relevant actions are prob- ably performed both for a person’s own sake and for the sake of a collectivity such as a team, department, or organization. Individuals may approach social situations with a wide range of moti- vational orientations that are neither purely individualistic (concerned only with one’s satisfaction) nor purely altruistic (concerned only with maximizing the other’s satisfaction). Deutsch (1973, in Shamir, 1990) uses the term collectivistic to refer to a motivational orientation that contains a concern with both one’s own satisfaction and others’ welfare.

The importance of discussing the linkages between individual motivations and collective actions stems from the increasing recognition of the importance of cooperative behaviors for organizational effectiveness. During the 1990s, hundreds of American companies (e.g., Motorola, Cummins Engine, Ford Motor Co.) reorganized around teams to leverage the knowledge of all employees. Now it appears that the concept is going global, and recent research conducted in Western Europe has supported the wisdom of teams. For example, the Ritz-Carlton Hotel Co. has created ‘‘self-directed work teams’’ with the goal of improving quality and reducing costs. In the hotel’s Tysons Corner, Virginia, facility, a pilot site for the company’s program, the use of these teams has led to a decrease in turnover from 56 to 35%. At a cost of $4,000 to $5,000 to train each new employee, the savings were significant. At Air Products, a chemical manufacturer, one cross-functional team, working with suppliers, saved $2.5 million in one year. OshKosh B’Gosh has combined the use of work teams and advanced equipment. The company has been able to increase productivity, speed, and flexibility at its U.S. manufacturing locations, enabling it to maintain 13 of its 14 facilities in the United States, which made one of the few children’s garment manufacturers able to do so (Gibson et al. 2000). This shift in organizational structure calls for higher cooperation in group situations. Cooperation, defined as the willful contribution of personal effort to the completion of interdependent jobs, is essential whenever people must coordinate activities among differentiated tasks. Individualism is the condition in which personal interests are accorded greater importance than are the needs of groups.

Collectivism occurs when the demands and interests of groups take precedence over the desires and needs of individuals. Collectivists look out for the well being of the groups to which they belong, even if such actions sometimes require that personal interests be disregarded. A collectivistic, as opposed to an individualistic orientation should influence personal tendencies to cooperate in group situations (Wagner 1995).

A core component incorporated in the new paradigm of leadership is that transformational leaders affect employees to transcend their own self-interests for the sake of the team, organization, or larger collectivity (Bass and Avolio 1990; Burns 1978). The effects of charismatic and transformational leaders on followers’ relationships with the collective are achieved through social identification, that is, the perception of oneness with, or belonging to, some human aggregate (Shamir 1990). People who identify with a group or organization take pride in being part of it and regard membership as one of their most important social identities. High social identification may be associated with a collectivistic orientation in the sense that the group member is willing to contribute to the group even in the lack of personal benefits, places the needs of the group above individual needs, and sacrifices self-interest for the sake of the group (Shamir 1990; Shamir et al. 1998). A charismatic or transfor- mational leader can increase social identification by providing the group with a unique identity distinguishing it from other groups. This can be achieved by the skillful use of slogans, symbols (e.g., flags, emblems, uniforms), rituals (e.g., singing the organizational song), and ceremonials. In addition, transformational and charismatic leaders raise the salience of the collective identity in followers’ self-concepts by emphasizing shared values, making references to the history of the group or organization, and telling stories about past successes, heroic deeds of members, and symbolic actions by founders, former leaders, and former members of the group (Shamir et al. 1993). Frequent references by the leader to the collective identity and presentation of goals and tasks as consistent with that identity further bind followers’ self-concepts to the shared values and identities and increase their social identification (Shamir et al. 1998).

Collectivistic appeals are illustrated by comments from Mary Kay Ash to her sales force at the company’s annual convention:

There was, however, one band of people that the Romans never conquered. These people were the followers of the great teacher from Bethlehem. Historians have long since discovered that one of the reasons for the sturdiness of this folk was their habit of meeting together weekly. They shared their difficulties and they stood side by side. Does this remind you of something? The way we stand side by side and share our knowledge as well as our difficulties with each other at our weekly unit meetings? . . . What a wonderful circle of friends we have. Perhaps it is one of the greatest fringe benefits of our company.

—(Conger and Kanungo 1998, p. 160)

By implication, Mary Kay is saying that collective unity can work miracles in overcoming any odds.

From Extrinsic toward Intrinsic Motivation to Work

A classic categorization for work motivation is the intrinsic–extrinsic dichotomy. Extrinsic needs demand gratification by rewards that are external to the job itself. Extrinsic motivation derives from needs for pay, praise from superiors and peers, status and advancement, or physically comfortable working conditions. Intrinsic needs are satisfied when the activities that comprise the job are them- selves a source of gratification. The desire for variety, for meaning and hope, and for challenging one’s intellect in novel ways are examples of intrinsic motivation. When one engages in some activity for no apparent external reward, intrinsic motivation is likely at work. There is evidence that extrinsic rewards can weaken intrinsic motivation and that intrinsic rewards can weaken extrinsic motivation. However, intrinsic job satisfaction cannot be bought with money. Regardless of how satisfactory the financial rewards may be, most individuals will still want intrinsic gratification. Money is an important motivator because it is instrumental for the gratification of many human needs. Fulfilling basic ex- istence needs, social needs, and growth needs can be satisfied with money or with things money can buy. However, once these needs are met, new growth needs are likely to emerge that cannot be gratified with money. Pay, of course, never becomes redundant; rather, intrinsic motivators to ensure growth-stimulating challenges must supplement it (Eden and Globerson 1992).

Classic motivational and leadership theories have emphasized both extrinsic and intrinsic rewards. However, transformational leadership theory goes beyond the rewards-for-performance formula as the basis for work motivation and focuses on higher-order intrinsic motivators. The motivation for development and performance of employees working with a transformational leader is driven by internal and higher-order needs, in contrast to the external rewards that motivate employees of trans- actional leaders (Bass and Avolio 1990). The transformational leader gains heightened effort from employees as a consequence of their self-reinforcement from doing the task. To an extent, transfor- mational leadership can be viewed as a special case of transactional leadership with respect to ex- changing effort for rewards. In the case of transformational leadership, the rewarding is internal (Avolio and Bass 1988).

The intrinsic basis for motivation enhanced by transformational and charismatic leaders is em- phasized in Shamir et al.’s (1993) self-concept theory. Self-concepts are composed, in part, of iden- tities. The higher the salience of an identity within the self-concept, the greater its motivational significance. Charismatic leaders achieve their transformational effects through implicating the self- concept of followers by the following four core processes:

1. By increasing the intrinsic value of effort, that is, increasing followers’ intrinsic motivation by emphasizing the symbolic and expressive aspects of the effort, the fact that the effort itself reflects important values.

2. By empowering the followers not only by raising their specific self-efficacy perceptions, but also by raising their generalized sense of self-esteem, self-worth, and collective efficacy.

3. By increasing the intrinsic value of goal accomplishment, that is, by presenting goals in terms of the value they represent. Doing so makes action oriented toward the accomplishment of these goals more meaningful to the follower in the sense of being consistent with his or her self-concept.

4. By increasing followers’ personal or moral commitment. This kind of commitment is a moti- vational disposition to continue a relationship, role, or course of action and invest effort re- gardless of the balance of external costs and benefits and their immediate gratifying properties.

The Full Range Leadership Model: An Integrative Framework Bass and Avolio (1994) propose an integrative framework that includes transformational, transac- tional, and nontransactional leadership. According to Bass and Avolio’s ‘‘full range leadership model,’’ leadership behaviors form a continuum in terms of activity and effectiveness. Transforma- tional leadership behaviors are at the higher end of the range and are described as more active– proactive and effective than either transactional or nontransactional leadership. Transformational leadership includes four components.

Charismatic leadership or idealized influence is defined with respect to both the leader’s behavior and employee attributions about the leader. Idealized leaders consider the needs of others over their own personal needs, share risks with employees, are consistent and trustworthy rather than arbitrary, demonstrate high moral standards, avoid the use of power for personal gain, and set extremely challenging goals for themselves and their employees. Taken together, these behaviors make the leader a role model for his or her employees; the leader is admired, respected, trusted, and ultimately identified with over time. Jim Dawson, as the president of Zebco, the world’s largest fishing tackle company, undertook a series of initiatives that would symbolically end the class differences between the workforce and management. Among other actions, he asked his management team to be role models in their own arrival times at work. One executive explained Dawson’s thinking:

What we realized was that it wasn’t just Jim but we managers who had to make sure that people could see there were no double standards. As a manager, I often work long hours. . . Now the clerical and line staff don’t see that we are here until 7 because they are here only until 4:45 p.m. As managers, we don’t allow ourselves to use that as an excuse. . . Then it appears to the workforce that you have a double standard. An hourly person cannot come in at 7:05 a.m. He has got to be here at 7:00 a.m. So we have to be here at the same time.

(Conger and Kanungo 1998, pp. 136–137)

Similarly, Lee Iacocca reduced his salary to $1 in his first year at Chrysler because he believed that leadership means personal example.

Inspirational motivation involves motivating employees by providing deeper meaning and chal- lenges in their work. Such leaders energize their employees’ desire to work cooperatively to contribute to the collective mission of their group. The motivational role of vision is achieved through the selection of goals meaningful to followers. For example, Mary Kay Ash articulates her company’s mission as enhancing women’s role in the world and empowering them to become more self- confident. This is a highly appealing message to an organization made up of women for whom selling Mary Kay Cosmetics may be their first working career. The importance of giving meaning to work is also illustrated in the speech of Orit Gadiesh, the vice chairman of Bain and Co., a well-known Boston management consulting firm. After a period of crisis, the financial picture of the company had turned around, but Gadiesh sensed that the organization had lost pride in itself. She chose the company’s annual meeting in August 1992 to convey in words what she felt the organization had to realize, a ‘‘pride turnaround.’’ Gadiesh said, ‘‘We’ve turned around financially, and we’ve turned around the business. . . . Now it’s time to turn around what they [competitors] really fear, what they have always envied us for, what made them most uneasy—as crazy as this sounds. It’s time to turn around our collective pride in what we do!’’ (Conger and Kanungo 1998, p. 182).

Intellectual stimulation entails the leader’s and the employees’ questioning of assumptions, re- framing problems, and thinking about concepts using novel approaches or techniques. For instance, Richard Branson, the charismatic British entrepreneur who built the diversified, multibillion dollar business of Virgin, sets an example of an innovative and unconventional approach to business. Time after time, Branson has found opportunities in established industries by going against conventions. One of his earliest successful initiatives was in discount stores. When approximately 20 years old, he observed that despite the abolition of a government policy allowing manufacturers and suppliers to ‘‘recommend’’ prices to retail outlets (which had ensured high prices for records), music records remained overpriced. He decided to challenge norms around pricing by offering records through the mail, discounting them some 15% from retail stores. When he entered the airline business in 1984, he distinguished himself from competitors in various ways from lower fares to in-flight masseurs, fashion shows to musicians, and motorcycle transportation to the London airport. Anita Roddick of The Body Shop also expresses a hard-line stance against the traditional practices of the cosmetics industry: ‘‘It turned out that my instinctive trading values were dramatically opposed to the standard practices in the cosmetic industry. I look at what they are doing and walk in the opposite direction’’ (Conger and Kanungo 1998, p. 185).

Individualized consideration represents the leader’s effort to understand and appreciate the dif- ferent needs and viewpoints of employees while attempting continuously to develop employee po- tential. A soldier in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) describes his platoon leader’s individualized treatment

On the way back, there was a very steep slope. I finished it with no air in my lungs. We still had 400 meters to run. I was last and I couldn’t walk anymore. Then, K., the platoon commander came and said ‘‘run.’’ I can’t walk and he is talking to me about running. Ten meters before the end he said ‘‘now sprint.’’ I did it and got to the camp. I felt great. I felt I had done it. Suddenly I discovered that K. was able to get me to do things that I never thought I could do.

(Landau and Zakay 1994, pp. 32–33)

Donald Burr, the former CEO of People Express Airlines, who was deeply interested in creating a humane organization and was guided by a fundamental belief in people, summarizes his view: ‘‘The people dimension is the value added to the commodity. Many investors still don’t fully appreciate this point’’ (Conger and Kanungo 1998, p. 144).

Conversely, transactional leaders exert influence on employees by setting goals, clarifying desired outcomes, providing feedback, and exchanging rewards for accomplishments. Transactional leader- ship includes three components. With the contingent reinforcement style, the leader assigns or secures agreements on what needs to be done and promises or actually rewards others in exchange for satisfactorily carrying out the assignments. Alternatively, using the management-by-exception—active style, the leader arranges actively to monitor deviations from standards, mistakes, and errors in the employees’ assignments and takes corrective action as necessary. With the management-by- exception—passive style, the leader waits for problems to emerge and then takes corrective action. Nontransactional leadership is represented by the laissez-faire style, in which the leader avoids in- tervention, transactions, agreements, or setting expectations with employees (Bass 1996; Bass and Avolio 1993).

One of the fundamental propositions in Bass and Avolio’s model is that transformational lead- ership augments transactional leadership in predicting leader effectiveness. Transformational leader- ship cannot be effective if it stands alone. Supporting most transformational leaders is their ability to manage effectively, or transact with followers, the day-to-day mundane events that clog most leaders’ agenda. Without transactional leadership skills, even the most awe-inspiring transformational leaders may fail to accomplish their intended missions (Avolio and Bass 1988). Indeed, several studies (Hater and Bass 1988; Howell and Frost 1989; Seltzer and Bass 1990) have confirmed this ‘‘aug- mentation hypothesis’’ and shown that transformational or charismatic leadership explained additional variance in leader effectiveness beyond either transactional leadership or leadership based on initiating structure and consideration. Sometimes, with highly transformational or charismatic leaders, there is a need to find a complementary top manager with a more transactional-instrumental orientation. For example, Colleen Barrett, the executive vice president of Southwest, is the managerial complement to Herb Kelleher’s charismatic, loosely organized style. She is a stickler for detail and provides the organizational counterweight to Kelleher’s sometimes chaotic style (Conger and Kanungo 1998).

Thus, according to the full range leadership model, every leader displays each style to some degree. Three-dimensional optimal and suboptimal profiles are shown in Figure 3. The depth fre- quency dimension represents how often a leader displays a style of leadership. The horizontal active dimension represents the assumptions of the model according to which the laissez-faire style is the most passive style, whereas transactional leadership incorporates more active styles and transforma- tional leadership is proactive. The vertical effectiveness dimension is based on empirical results that

have shown active transactional and proactive transformational leadership to be far more effective than other styles of leadership. The frequency dimension manifests the difference between optimal and suboptimal profile. An optimal managerial profile is created by more frequent use of transfor- mational and active transactional leadership styles along with less frequent use of passive transactional and laissez-faire leadership. The opposite directions of frequency create a suboptimal profile

Comments

Post a Comment